Why REST isn’t Always Best

By Oscar Diosdado / 12/01/2020 / Infrastructure

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT: Opinions in this content reflect those of the author. Unless specifically noted in the article, GM Financial is not affiliated with, does not endorse, and is not endorsed by any of the companies mentioned. All trademarks and other intellectual property used or displayed are property of their respective owners.

The Stratos Portal is in an in-house application we developed to provide the capabilities of a cloud management portal (CMP) for our on-premises cloud hosted on VMWare. It is currently used by our IT architect team to request infrastructure such as VMs and server roles with the goal of the product to be a self-service for all on-premises infrastructure, like firewall rules, VIPS and storage. The portal automates most manual steps that occur when delivering infrastructure from inception down to the server support team that ultimately manages the VM long-term. The portal is built using React for the front end and Node for the backend API. We followed the 12-factor principles that lend themselves to be able to be containerized and thus run on any hosted platform.

The Problem

When a user logs in to the portal to submit a request for a VM, they are guided through an order form that creates a JSON payload of this data that is then submitted to the backend.

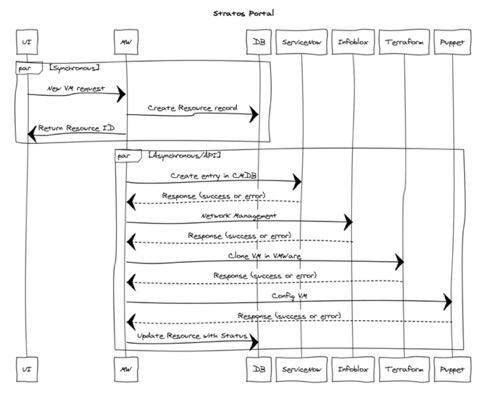

In the first iteration of the platform, all calls to the external services, such as Infoblox for network management, Terraform for VM cloning, ServiceNow for CMDB management, and Puppet for configuration, were handled by the backend.

Communication from the front end, backend, and the third-party services are all handled using REST. A few months after going live, we discovered that this wasn't always ideal for our case. Here's what we learned:

REST is statelessness

A user’s request from the front end to the backend is handled in a synchronous fashion; the backend API receives this request and then launches calls to perform these actions in an asynchronous fashion where applicable.

Building a VM has steps that can happen asynchronously, but these are found during the end of the process. By design, REST communication is statelessness, meaning that once a request is received by the API, it should not keep its client state on the server.

So, what happens if one of the third-party services is down? Or if there is a new change or misconfiguration downstream? Or worse, what if our container crashed? In our first iteration of the platform, this type of change or interaction caused a build to fail with no way to recover.

Once a root cause of the failure was determined, the build had to be decommissioned and a new one requested. This caused a lot of manual work for our team and also delayed the IT architects in being able to deliver the infrastructure.

The Solution

We could have leveraged retry mechanisms that are available in the node REST libraries, but this would have solved only one of our problems. The retry functions would still only exist on the single transaction. Once the retry was exhausted, we would have lost that transaction with no way of restarting. What we needed was a way to pause the process when a critical error was encountered and continue once it had been addressed. We needed a solution that would track state.

Enter the Rabbit, MQ

Message queues are not a new thing. Java Message Service (JMS) was first introduced back in 1998 and the advanced message queuing protocol, which is the standard for message-oriented middleware, was created in 2003 by John O’Hara. It sought to define a standard for message orientation, queuing and routing as well as to introduce reliability and security.

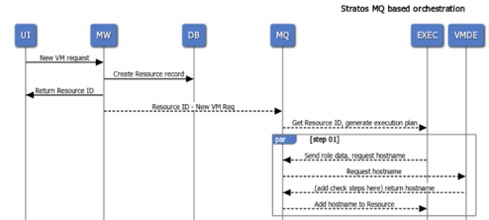

Messages would allow us to move singular transactions between functions, i.e., calling Terraform function with Infoblox data to build a relationship between the server and the message broker where a message would be placed on a queue that the Terraform service worker would subscribe to. The worker would process the work needed and reply back to another queue to continue the build process.

In this architecture, third-party services would have their own workers that would subscribe to the third party’s own queue. An executor would be the orchestrator between the workers and would handle the initial message creation and updates to the status of the resource being built.

Going forward

Re-architecting an application is difficult enough, and doing it while still providing bug fixes to your end users is even more challenging. Our approach is to break these processes down slowly using the strangler pattern. Yes, even a shiny, new 12-factor app can become a monolith. More to come on how we are tackling this in future articles. Stay tuned!